Changes in how Anglo-American culture has understood intergenerational sex can be seen with startling clarity in the life of British writer Norman Douglas (1868-1952), who was both a beloved and popular author, a friend of luminaries like Graham Greene, Aldous Huxley, and D.H. Lawrence, as well as an unrepentant and uncloseted pederast. – From the publicity for a new biography of Douglas.

Hang on, we might think, that can’t be right, can it? How could this writer guy have been openly attracted to kids – and very sexually active with pre-teens, as it happens – while also being a commercially successful, well regarded writer? Whoever heard of a “popular pederast”? It’s a classic oxymoron!

Scandal and disgrace caught up with Douglas soon after his death, though, which had a big impact on his literary as well as personal reputation. Unlike Lawrence and the others mentioned above, he became unmentionable in polite society; people just stopped reading him and in time he was simply forgotten.

As a member of impolite society, however, I heard about him. Maybe thirty years ago I read his novel South Wind, published in 1917, when it was such a great success it is said a whole generation was brought up on it. It went through seven editions rapidly, “achieving startling large-scale success”, according to Orel’s Popular Fiction in England. A true best seller, in other words.

Set on an imaginary island off the coast of Italy, it portrays a thinly fictionalized Capri (where Douglas lived for many years, being eventually awarded honorary citizenship) and its denizens. The South Wind of the title is the Sirocco, which wreaks havoc with the islanders’ sense of moral propriety. I found it quite charming and amusing, but not particularly shocking or memorable. I can only suppose its huge early success arose from it being felt at the time as an invigorating breath of fresh air, blasting away the cobwebs of Victorian stuffiness, rather than a gentle, soporific southern breeze.

Far more sensational than this novel, though, was the life of Douglas himself, so I was thrilled to hear about the new biography mentioned above: Unspeakable: A Life beyond Sexual Morality, by historian Rachel Hope Cleves. I quickly ordered an advance copy ahead of its scheduled publication early last month. But five weeks later I am still waiting! The website of the publishers, the University of Chicago Press (UCP), now shows December as the publication date. Their customer services have not responded to an email requesting further details.

Has controversy caught up with this title already? Is it threatened with cancellation? A Zoom promotional event organised by UCP went ahead as planned, about a week after the delayed launch. This gave me the opportunity to ask the author what was afoot. She thought the delay was just down to Covid-19, but as the weeks slip by this becomes less convincing. Who knows? UCP could be a house divided, with the marketing people ploughing on gamely while others are getting cold feet.

Extreme nervousness was palpable in the promotion itself, which was billed on the Eventbrite platform as the author in conversation with another biographer, Alexis Coe. In the role of presenter and interviewer, Coe was treading on eggshells from the start, announcing in her introduction that this had been a difficult book to write and publish, and that “We are going to be uncomfortable in this conversation.”

And how! Without even asking the views of any of us among the 38 participants, who appeared to be mainly postgrads and early-career academics, Coe declared that “everyone” in the forum “is likely to have a hard time understanding that Douglas had mutually loving relationships with boys”. Also, the event, scheduled to last a generous three hours, was hurriedly wound up after less than half that time, after taking only a few participants’ questions. I was among those who wanted to ask more, as you may imagine, but never had the chance.

We did learn quite a lot about Douglas and his circle, though, based on a book which appears to take a bravely non-judgemental view of his pederasty. Rachel Hope Cleves started by saying Douglas was “remarkably honest about his sexual life, in his writing and conversation and in practice.” He kept no secrets about this from anybody and he left a remarkable archive.

The word paedophile does not occur in the sources from Douglas’s life, we heard. Cleves said she avoids the term herself in this historical context. She talks about “intergenerational sex” rather than child rape. She doesn’t talk about “victims” or “survivors” or “abuse” either. Very refreshing!

We heard that Douglas liked boys on the cusp of puberty but not yet pubescent, from around eight years old to 10 or 12. “I’m sorry if that makes people uncomfortable,” she added, doing her best not to sound uncomfortable herself. There were also many sexual encounters with young girls and adult women. She had chosen the word “encounters”, she said, as a deliberately neutral one, that did not exclude the possibility of either coercion or affection.

A number of these affairs would last a couple of years or more until the boy was 14 or 15. These youngsters would often remain friends with Douglas long after that. He became a father-figure to some of his former lovers. After they grew up and married, he would visit their wives and children.

Coming across as a typical modern victim feminist, Alexis Coe said that a hard part of the book for her to understand was that Douglas didn’t just appeal to his fellow male writers but also to women, including radical feminists of the day.

Yes, said Cleves, rule-breaking radical women were big fans because he was a huge advocate of gender and sexual liberalism. These women included anti-fascist activist and shipping heiress Nancy Cunard, whose lovers included black poet Langston Hughes, celebrity food writer Elizabeth David, and Annie Winifred Ellerman (the poet “Bryher”), a highly influential intellectual at that time.

Douglas himself was a cosmopolitan figure from a wealthy family of Scottish lairds, with the polished, easy manners to go with his pedigree, and a lively wit – although his jokes were “awful”, according to Cleves, no longer resonating in 2020 as they would have a century earlier. Part of his charm, she said, was simply being himself at a time when the range of acceptable sexual expression was very narrow, confined essentially to conventionally married couples. Those outside what Gale Rubin calls the “charmed circle” of mainstream sexual acceptability thus became available as fellow travellers. He was a standard bearer for everyone who opposed conservative sexual norms.

That was about it for the main Coe-Cleves “conversation”, apart from a brief and poorly substantiated reference Cleves had made to Douglas treating his wife very badly. I was sceptical about this, because all the other evidence points strongly to him having been a nice guy, much loved by everyone, of all ages and both sexes. It was as though Cleves, having stuck her neck out to give a daringly positive view of his “pederasty”, felt the need to monster Douglas in some other way, mainly perhaps because she senses that the public these days is beyond persuading that a pederast – or paedophile – could possibly have been a truly pleasant person.

Most of the questions “from the floor”, indeed, reflected this prejudice: Did Douglas focus his attention just on poor, easily exploited boys? Answer: no. What about his “commercial” sex? Again, nothing sordid to report. Yes, he had sex with boys to whom he gave money and presents. When he went to the resort island of Ischia, near Naples, in successive years, the kids he’d had sex with the year before would track him down, to renew acquaintance – not just for the money but for his company, sometimes fighting among themselves to be with him.

There was original source material to confirm this, she said; but the evidence for mistreatment of his wife turned out to be rather vague and second-hand. In a written question posted in the Zoom chat space, I asked:

Douglas’s affectionate sex/friendships with boys seem fine to me. I’d have a bigger issue with his mistreatment of his wife, if that’s what it was. Also his own children. Was he a bad father?

Alexis Coe could not bring herself to acknowledge that there was anyone in the audience who would be “fine” with the BL stuff. Instead, she translated my question by saying to Cleves: “There is curiosity around his children, his wife. Can you summarise those relationships?”

The answer Cleves gave was lengthy but to my mind unconvincing. The available sources gave mixed messages, she said. We would just have to read the chapter on the marriage in the book and make up our own minds. There are some solid facts, though. Norman was no slouch in bed with his wife Elsa: she was pregnant on their wedding day and they soon had two sons. So, the marriage was clearly not an unconsummated sham. After about five years there was a divorce, granted on the grounds of Elsa’s adultery. Norman was awarded custody of the boys, Archie and Robin, who remained loyal to their father throughout their adult life. Hardly a damning indictment.

Unsatisfied with Cleves’ version, at huge expense I bought a quite rare old ex-library copy of an earlier Douglas biography by Mark Holloway, published in 1976. After checking all the index entries on Elsa and the marriage, I see some source material that could be interpreted against Douglas but it is thin stuff in an otherwise very full work of some 520 pages.

What is really important, though, is not Cleves’ opinions, nor even her book. No, the pure gold on Douglas is to be found in the “remarkable archive” to which she referred, especially a collection of letters sent to Douglas over the years by his young lovers. Cleves has written about the intimate child-adult relationships in question, not just in her as-yet-unseen book but also in an academic article I have been able to get hold of. One such friendship was with a boy named Eric Wolton. Here is what Cleves said in her article, which includes a very revealing quotation from the boy himself as a mature adult looking back:

Douglas picked up Wolton at a 1910 Guy Fawkes celebration at Crystal Palace in southeast London. Douglas was forty-one, soon to be forty-two. Wolton was twelve. Judging from the contents of Douglas’s pocket diaries, the relationship was sexual, and likely transactional, from the outset. Sex work was not an unusual means of making money for working-class London boys before the 1920s, and “certain relationships were accepted in working-class neighborhoods,” according to Matt Houlbrook. Douglas and Wolton’s relationship swiftly developed beyond an ephemeral encounter into an affective companionship. Douglas sought the permission of Wolton’s parents to take the boy on a walking tour through southern Italy. They had been intending to send Wolton to reform school, and gladly accepted Douglas’s offer of private tutelage instead. After the two returned from the trip, both sick with malaria, Douglas delivered Wolton to his parents and then went to recuperate at the house of his friend Joseph Conrad. But Wolton wrote to Douglas that he was “longing to see your old dear face again.” Soon the pair were reunited. They lived together and traveled together intermittently during the next couple of years. When World War I broke out, Wolton enlisted. Douglas’s sexual attentions by then had moved on to younger subjects, but the two remained close throughout their lives.

A decade after they first met, Wolton, who was then in his early twenties, wrote to Douglas reminiscing about their former times together: “Doug, I have wanted Italy and you as bad as anything last week. All the old times flash back in my memory.” Wolton refused to disavow his childhood sexual relationship with Douglas, writing:

They were happy times too Doug were’nt [sic] they, I have no evil thoughts about them although I am different today than I was then. You were my tin god and even now you are. I do really love you as a great friend and even now I know that if I live to be a million never shall I harbour the same feeling that I have for you… I am afraid I have expressed myself very badly but I want you to understand Doug that you are more to me than ever you were. The difference is now that I am old enough to realise it.

As an adult, Wolton pursued sexual encounters with women. He was “different” than he had been as a boy, but he felt positively about his youthful sexual encounters with Douglas nonetheless.

Let us end by noting that Eric Walton was awarded the Military Medal for bravery during the First World War. After the war he took up a post with the police in British-administered Tanganyika, later rising to Chief Superintendent. Presumably, judging by his continuing warm friendship with Douglas, he did not use his police position to launch a crackdown on “pederasts”! Nor does there seem to be any reason to believe Douglas had ruined his life. Far from it.

FROM HERETIC TOC TO TIKTOK

Many here will know “Zen Thinker” as a regular Heretic TOC commentator. Today, he offers some interesting thoughts on a far more high-profile “tic toc”: TikTok. Zen Thinker has a background in finance; he is a GL and has major interests in music, film and tennis.

I have mentioned that youth, both teenagers and children, are developing new art forms on the TikTok platform. TikTok is incredibly new, having become mainstream in 2017/18. There is emerging the short video form, sometimes only a few seconds, which is highly choreographed and often highly polished, whether dance or some other form such as playing a musical instrument. The emergence of this new Art is important for empowering children and involving them in the culture. For too long children have been without a voice. We have seen a smattering of child actresses and singers, maybe the odd painter and even a composer, but this brings artistic involvement to the forefront for children. Many little girls attend ballet classes, and are involved in gymnastics, and truly, this is a form of art in its own right. But TikTok is something new, and impressive at the same time.

Teenagers are the most common artistic contributors to TikTok, especially eighteen-year-olds I think. But there are also many younger users and content developers, often as young as seven. A girl called Amelia [actual names have been changed] who is seven has a truly awesome page where her videos are highly polished, creative and inspired; as far as I know she runs her own channel, with minimum parental involvement. A girl called Ada, eight, definitely runs her channel entirely off her own steam. It seems there is rarely parental permission required for such a thing.

Now these little girls typically get far less views than the more popular teens, but I don’t know how much at risk they are from unwanted communications. It seems you can message anyone on the site, although I have studiously avoided that. I’m also cautious about causing a spike in views on a small account, as that may look irregular to the content creator. But let us discuss the particular quality of their TikTok performances.

It seems that possibly for the first time in world history, little girls are creating an art form en masse which is readily available to any member of the public. It typically involves highly choreographed dance to an overlaid music track, although there are variations on this. But take the seven-year-old, Amelia: her TikToks are very highly developed in artistic and creative merit – she is beautiful, precocious, and confident. Ada has far less views but her TikToks are interesting, and she is pretty.

Let’s think through the implications of this. Little girls creating unique and meritorious Art is a brand-new thing – although ballet and gymnastics have existed for an incredibly long time, this is more a form of direct connection with an audience. Children are gaining autonomy, confidence, and their own voice. This can only be a good thing. I think the best chance of a connection with the spirit of children is not in real life but online. Obviously there is the danger of illegal forms which is a current issue for law enforcement, but that is not of concern here. I am far more interested in the safe, legal, artistic expression of little girls, and this is a global phenomenon: I have seen Brazilian pages too for example.

The ultimate implication is quite radical: that little girls for the first time have a voice, quite independent of parental influence. This is entirely new. The form of that voice is currently quite limited but the creative expression is charming and beautiful. Who knows what comes after TikTok, but for now we can celebrate the existence of this voice and the implications for juvenile independence.

WRESTLING WITH BOREDOM

Heretic TOC has no hesitation in awarding News Photo of the Year to the wonderful shot you see below, one of several great pictures taken in the Oval Office at the White House by Reuters. All of them can be seen here, in The Sun’s report of a ceremony at which outgoing (eventually!) US President Donald Trump awarded wrestler Dan Gable the Medal of Freedom, with Gable’s 13 grandchildren present in person – but not necessarily in spirit! As the report puts it, the wrestler’s “naughty but charming grandchildren stole the spotlight”.

Posting links to reviews of Rahel Hope Cleves’s book here, in case anyone (like me!) enjoys looking back through previous posts.

First, see http://wapercyfoundation.org/?page_id=1056 at the William Percy Foundation’s book reviews section.

Second, see https://greek-love.com/biographies/pederasty-biography-reviews/unspeakable-a-life-beyond-sexual-morality

These 2 reviews really complement each other.

The scholar who runs the Greek Love site has also reproduced letters from Eric Wolton to Douglas; see – https://greek-love.com/modern-europe/norman-douglas-1868-1952/letters-from-eric-wolton-1921

For the interested reader there’s more:

Always more to learn about!

Honestly, what I find amazing is that people are surprised that relationships like those which Doug Norman had took place, and without a doubt continue to take place. (And you too, Tom, for that matter.)

Human sex and sexuality isn’t just about genitalia and their function (yes, I’m repeating something most or all people here are well aware of), it’s about the actual contact … which is something that can be enjoyed at any age, and which can take any old person any old where if it happens, irrespective of their “sexuality”.

Hence, to hear that even the author of this biography was tweaked with discomfort, just discombobulates me.

On another matter: a bit tedious to have to fill in the who I am stuff, but it wouldn’t let me do it any other way. Sheesh, I must expect too much of our dull computer friends.

Good to hear from you, Bruce, but mystified by this:

>On another matter: a bit tedious to have to fill in the who I am stuff, but it wouldn’t let me do it any other way.

What do you mean? If the computer is being bossy, I’ll see if I can have a word with it: put it in its place! 🙂 Trouble is, it might end up putting me in my place! 🙂

Inspired by your post, I tracked down some works by Norman Douglas from my local library. I can’t say I was particularly delighted by what I discovered: indeed, I’m inclined to think that the old boy’s sexual preferences may be the least offensive thing about him. To my eyes, his writing breathes an airy colonial arrogance, especially when he’s writing about non-Europeans (his monograph on French colonial Tunisia, Fountains in the Sand, is a masterpiece of orientalist condescension), but he is scarcely less oblivious to the realities of the people he is living among when he turns to his beloved Italy. He exudes the air of an Englishman abroad who views the locals at best as a nuisance and at worst as vandals and despoilers of a classical legacy to which he (Douglas) is the true legitimate heir.

For a travel writer Douglas displays an amazing lack of perceptiveness and curiosity; only his prejudices seem to be inexhaustible. He is in love with an imagined past, and somewhat callous towards the sufferings of the present. The demands of Italian socialists and reformers can always be dismissed as the contemptible rabble-rousing of arriviste politicians and outcaste journalists. He has a particular neo-pagan distaste for all kinds of monotheism – Islam in particular, but also ‘sunless’ Christianity and Judaism. In one of his later works he suggests with all apparent seriousness that Christianity is to blame for Soviet Communism (envy of the rich, apparently) and the Jews for Nazi Fascism (because ethnic chauvinism begins with Ezra and Nehemiah)! It’s hard to know whether to laugh or cry at this sort of thing.

It is possible, of course, that for all his pig-ignorance and prejudice, Norman Douglas might have been a kind and considerate boy-lover. But that is not really the impression of him that I get from his writing: he comes across as just another vain and superior Northerner quite willing to have sex with boys whose culture and people he openly despised. (He is, admittedly, in a long and rather disreputable line of such holiday-pederasts.) It is cheering to know that he did in fact have positive relationships with some of his younger lovers, but Douglas’ attempt to style himself as a cheerful Epicurean satyr appears rather distasteful and rather deluded to my eyes. In the hands of a better and more self-aware writer, this kind of self-styling might appear charming. But Douglas does not have the power to charm.

Kit, you wrote:

Which is pretty much what I concluded about Michael Jackson at the end of my book on his sexuality! 🙂

Saints, unfortunately, are in short supply generally, not just among child lovers, so I do not think we should be too surprised and disappointed if our heroes, or standard bearers for child-love, turn out to have their limitations, especially the ones they share with pretty well everyone else in the culture that once celebrated them.

It is no accident, surely, that the travel writing you find so distasteful was precisely what made Douglas so popular in his day. Colonial arrogance? Orientalist condescension? How his readers must have loved it!

Seen against this background, Douglas was simply a man of his times, wasn’t he? Hence no reason to single him out for personal opprobrium.

Turning to your particular criticisms, I am surprised to find I actually have some sympathy with Douglas as you represent him, especially as concerns his seeing the Italians as “vandals and despoilers” of their classical legacy. As a 17-year-old, visiting Italy for the first time on a school trip in 1962, I was shocked and saddened to see the dilapidated state into which the Italian state had allowed its Roman antiquities to fall, especially in Rome itself. The modern Italians did not strike me as worthy heirs.

And the shortcomings of monotheism? Right on, Norman! (or “Doug” as at least one of the boys called him). With you all the way, man!

As for his claim that ethnic chauvinism began with Ezra and Nehemiah he was certainly wrong, but the easiest way of proving him to be so actually strengthens his underlying point: it is in the book of Joshua, somewhat earlier in the Bible and the associated historical/legendary narrative, that the most unequivocal, the goriest, the most downright genocidal ethnic chauvinism is evinced.

Sorry if this makes you laugh and/or cry!

As a Douglas devotee, I feel I must say something in defence of the man. It is difficult to know precisely how to refute your allegations, since your piece is rather subjective and impressionistic, and refreshingly evidence-free. But let me deal with just one or two of your assertions.

Let us begin with the charge of ‘imperialism’: You write that ‘his writing breathes an airy colonial arrogance, especially when he’s writing about non-Europeans (his monograph on French colonial Tunisia, Fountains in the Sand, is a masterpiece of orientalist condescension)’

I suggest you read ‘How About Europe?’ This was written by Douglas in response to Katherine Mayo’s ‘Mother India’ in which Mayo judges India to be deficient by Europe’s supposedly superior standards. Douglas was so irritated by this book, that he wrote ‘How About Europe?’ in response, arguing that India is superior to Europe in everything that makes for civilisation. Douglas has no time at all for any sort of assumption of European cultural superiority. His view of imperialism is clear: ‘I think, however, that Imperialism is an undiluted mischief, and that all its offspring are mischief.’ (p. 33) Douglas liked William Hickey’s memoirs of Anglo-Indian life in the eighteenth century, because they show that in Hickey’s time there was no social disapproval of a European marrying an Indian (‘Let him try it on, nowadays…’ he observes, p. 76). He rejects racial theories: ‘Whoever still believes in the immutability of racial characteristics… should read these memoirs in order to see how differently an Englishman near to us in point of time could think and behave.’ (p.77) He likes Hickey’s memoirs because in them ‘I observe no disparagement of native life or customs – indeed, older travellers to the East and older residents there are altogether lacking in our tone of arrogance towards Orientals. When did our racial superiority over them begin to dawn on us? When our racial intelligence began to decline.’ (p. 81) He says the following about Europeans in the Pacific: ‘Whoever reads Isles of Illusion will learn how European missionaries are “very largely responsible for the wiping out of hundreds of villages”; he will learn how “the horrible octopus of missionary-cum-trader-cum-official had spread his tentacles everywhere.” The White Man creeps over these regions like some foul skin disease… Why does one belong to such a race, so sad and yet so ferocious?’ (pp. 259-260)

As for Europe, we are over-governed, too conformist, have too much legislation and not enough leisure: ‘There is as much grace and dignity in a European existence just now as there is in a fat bourgeoise running after an omnibus.’ (p. 158)

His indignation at cruelty is palpable. Take this bitter irony on a section about the death penalty:

‘As we have a fit of age-raising just now we might consider, I think, whether it would not be reasonable to raise the hanging age, which is at present fixed at sixteen. It is difficult to conceive in what circumstances a boy of sixteen can deserve death by hanging. Yet during the twenty-five years ending 1926, fifty-seven persons under 21 were sentenced to death, and twenty of them actually executed. And while we are about it, we might raise the age of criminality in general. As matters stand, a child above seven who commits an offence against the law is a criminal. I gather from Mr. Brockway’s “New Way with Crime” that a departmental Commission which lately reported on this imbecility has concluded that the age “could now be safely raised to eight.” Perhaps seven and a half would meet the case.’ (pp. 60-61)

On pp. 86 there is a piece against the imprisonment of debtors. He also returns to his theme of the harshness of the law towards children: ‘[A]lthough everybody is agreed that prison life is harmful to persons under 21, yet the average sent there is 3000 a year… The other day a boy of 17 was sentenced to six months’ hard labour; another of 15 sent to prison for a month for stealing fourpence.’ (pp. 86-87)

He rails against the cruelties shown to children in French and English reformatories. These institutions do not exist in India. As for Moslems: ‘Mohammedans, who consider that children, however obstreperous or perverse, are their parents’ flesh and blood, would be horrified at such methods.’ (p. 105)

It is certainly true that he regards monotheism as objectionable. A god who ‘remains awake and responsible for all that happens on earth is a monster. Even with the help of the Devil to explain away the worst of his tricks, he cuts an indifferent figure.’ (p. 118) Monotheism, to Douglas, is ‘a graceless and unreasonable belief’ (ibid). But he prefers Roman Catholicism, because they have essentially gone back to polytheism, with the cult of the Blessed Virgin, the saints, etc. Furthermore, ‘Catholic countries contain no prudes, and their inhabitants know nothing of our obsession with this kind of morality… We have too much sex on the brain, and too little of it elsewhere.’ (p. 201)

Your charge that he dislikes ‘Islam in particular’ is nonsense: ‘There are no false notes in Mohammedanism, no patches. It simplifies our existence, and scorns its calamities. Above all, you have the joy of finding yourself among real men. This religion has not sapped our amour-propre…’ (pp. 122-123)

On pp. 124-125 he emphatically states the superiority of Chinese civilisation over Europe as well. He quotes Lowes Dickinson with approval: ‘The West talks of civilizing China. Would that China could civilize the West!’

He did not ‘openly despise’ Italians or Italian culture at all. Would you care to come up with a piece of evidence for this assertion? On the contrary, he liked Italy far more than England. It is true that his travel books are not exposés of social abuses. That was not their purpose, and would not have entertained his readers. He has plenty of curiosity, in my opinion, but the 19th/early 20th century genre of travel literature was not about producing a Baedeker. It was about the author’s own impressions and reflections. Douglas was valued because his writing was elegant, civilised and erudite, but with the hint of a satyr underneath it all.

All this is not to say that Douglas has all the politically correct opinions. He does not (and, frankly, this is one of the reasons why I like him). He is quite tough on those whom he thinks should be subject to Darwinian selection: ‘Our Statute Book is growing into a sinister contrivance for the conservation of fools. It is saturated with the delusion that men must be protected not only against each other, but against themselves.’ (p. 212) Like many others of his time, he thinks that the unfit are being invited to breed, thus diminishing the standards of the race. But this was a fairly prevalent obsession at the time. Bertrand Russell expressed the same anxiety in ‘The Principles of Social Reconstruction’ (pp. 124-127, Unwin, 1980)

By the way, the idea that Judaism is a distant ancestor of Nazism was not Douglas’s theory, but Oscar Levy’s, though Douglas was inclined to agree with it. Levy’s idea was that Judaism had originated the idea of the Chosen Race which must be kept racially pure (the book of Ezra forbids all intercourse with foreign women). Neither Levy nor Douglas were blaming contemporary Jews for their own persecution – obviously! The connection of the New Testament with Bolshevism was the other part of Levi’s thesis. (A similar connection is made by Bertrand Russell in his History of Western Philosophy, p. 361, Unwin, 1984)

It is true that Douglas disliked the idea of socialism, which he identified with the Webbian bureaucratic state. He feared that in such a society the state would become all-powerful. He was not alone in thinking this, and his concerns do not, to my mind, mark him out as wicked.

I haven’t got time to go into everything that contradicts your assertions. Life is too short. I shall have to leave it there. I agree, however, with what Tom O’Carroll has already said.

Lots and lots of relevant information! Thanks so much, Diogenes, for going to the trouble. Love it! Also very gratifying to have such a distinguished philosopher turn up here! 🙂

I’m watching this excellent documentary about teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p090xz9z/i-am-greta

Before it started I-player warned me that it wasn’t suitable for viewers under 16. How absurdly ironic!

Further to my piece, I’ve done a bit more research. It seems the children on TikTok follow each other in clusters, although many of the standard search tools have been deliberately disabled, e.g. ‘little girl’ in search returns nothing. Also, many of their accounts are starting to get banned for ‘violating community guidelines’, which must refer to the age requirement. Some idiots obviously think it is constructive to get these accounts banned. Having said that, some sketchy and dodgy-looking accounts are following some of the children. I genuinely don’t know how safe TikTok is.

All I want to do is appreciate the art and creativity produced by some of the girls – being minor attracted, I find this fulfilling. I think this is entirely harmless in itself, and I condemn any predatory behaviour.

That book reminds me of that one, The Man They Called a Monster, about Clarence Osborne.

> Children are gaining autonomy, confidence, and their own voice.

A fellow, who happens to be GL, told me that it came to his notice that a girl aged 12 has a “sexual education” Tiktok profile. No illegal content is present and she does not show her face. Her purpose is to answer questions from peer-aged followers regarding their own self-discoveries. One follower asked her if one could get pregnant during masturbation and she said no, mentioning that she did it daily. My friend also said that someone implied that she is too young to be doing such thing. She said “don’t preach to me”, but in Portuguese.

I don’t use Tiktok, so I don’t know the girl. But I think her profile won’t last long, since you need to be 13 to use Tiktok, as far as I know. Any content producer in that platform may be banned from it, if they are under the age of 13. Judging from what you described, such rule seems to be selectively enforced by the Tiktok community. So, I’m almost certain that the 12-year-old girl I mentioned will be reported and banned soon, since what she is doing is seen under a negative light by older users, who probably have already reported her to the administration.

>But I think her profile won’t last long, since you need to be 13 to use Tiktok, as far as I know.

It is conceivable she might actually be 13 but is aiming to appeal to others slightly younger and perhaps more in need of basic sex education! Even in that case, though, there will be no shortage of self-appointed sex police keen to stop her.

I know of many accounts run by seven and eight year olds. They are easily discoverable. TikTok seems very relaxed about the rules. However, out of respect for the children concerned, I don’t add myself as a follower to their accounts, or of course message them.

There was something in the news today about a data action brought by a twelve year old girl:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-55497350

So there are certainly forces at work trying to ban under-13 accounts, but for now there are many of them. The key is to show them respect, and then they may not be removed.

The idea of a 12-year-old girl suing Tiktok reminds me of a news story I heard here, about a girl aged 13 announcing she would hire a lawyer to free her adult boyfriend from jail, after the relationship was discovered.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A0L17QGCw2k

Might be of interest.

It’s great to see young people standing up for their rights in this area. I hope she stays safe and is successful.

I hope she remains safe. It’s quite an old news report, so she must be already legally able to consent (age of consent is 14 here).

I just want to ask Tom what he knows about all these Indian dancing boys. There are some videos out there where they are scantily clad and often dancing in a provocative manor. Anyone know the history on this, maybe there is more info out there then with the ‘Mascots’.

Well, H-P, as the population of India is well over a billion and the country itself is huge, “all these Indian dancing boys” could mean rather a lot of boys in rather a lot of places! Actually, if we consider the whole Indian subcontinent there is even more scope, with a lot more boys and a lot more dancing.

I don’t know about the videos (presumably you mean on YouTube etc) but I do know about live performances, having seen a few myself, notably in Kandy, in Sri Lanka, and Kochi, in the southern Indian state of Kerala.

In the latter case, I was a guest of the state government at the time – and, no, I do not mean a guest as in “a guest of Her Majesty”: I was a properly honoured guest, not languishing in an Indian prison! 🙂 I was a journalist at the time, which would have been in the late 1990s, and I had been invited by the Kerala government to sample the delights of the region with a view to me and other travel writers on the tour doing write-ups that would be favourable to their tourist industry.

Among those delights were some fabulous hotels, great cuisine, lots of interesting places to visit and… dancing boys! The Kerala tradition of Kathakali dance drama certainly includes boy dancers. Many of the boys I saw performing were indeed very scantily clad although I cannot remember whether they were doing local Keralan dances at the time. They may have included Sri Lankan dance in the show, which lasted for some hours. As I know from Sri Lanka, the best eye candy is the boys from Kandy! You wouldn’t know it from the Wikipedia page on Kandyan dance, though. All reference to boys appears to have been censored out!

Yes I think I went to Kandy, when I was there and was looking around Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic. It was near to where my guide’s family lived so my trip was combined with a visit to a small mountainous village. Jaffna in the North was a good place to visit. There was a large Fort there.

Thank you very much Tom for sharing this publication, I find Norman’s life very interesting, I imagine that his conversations with Huxley would go beyond social and moral perceptions.

Without a doubt, another author denigrated by beauty itself, from which he seems to run away, perhaps because of the same lack of understanding of the sacred.

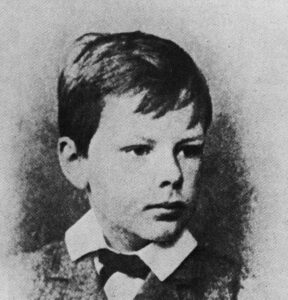

That’s just it, the change of perspective in the Anglo-American culture. More authors like these need to be known, to encourage visions of experience and their contextualization in relation to “greek love”.Very nice picture with the boy. Nice

My best wishes.

I leave a link that I think is appropriate to supplement: https://www.greek-love.com/modern-europe/italy/a-meeting-of-three-like-minds-in-capri-1951#_ftnref5

Thanks, LTEOGNIS, for your contribution, including the link to Greek Love Through the Ages, which is indeed an excellent site on this topic and BL history in general.

Yes ,thanks, LTEOGNIS. This link enables me to correct my quote (see below). It should have read: ‘a very small possessor attached to a very large possession.’

“Coming across as a typical modern victim feminist, Alexis Coe said that a hard part of the book for her to understand was that Douglas didn’t just appeal to his fellow male writers but also to women, including radical feminists of the day.”

I noticed that a lot of the articles (mainly in French) about the Matzneff affair had the same insistence on the “incomprehensible” support and even friendship of some French feminists for an avowed pedophile.

I remember reading about Norman Douglas in Michael Davidson’s autobiography The World, the Flesh and Myself. But almost the only specific thing I remember about him is (and I quote only roughly from memory, as I no longer have my copy of the book) that he said he ‘liked a very big instrument on a very small person’!

“We heard that Douglas liked boys on the cusp of puberty but not yet pubescent, from around eight years old to 10 or 12.”…

…That’s Me, also!

I love these kinds of posts…You’re being a historian here, Tom! And for a group in desperate need, of reconnecting to their natural history.

That was truly a whole other world, from the hell we are in today.

I’ll look for that book.

Oh!…and looking at that first picture, that clearly is not a boy abused by Douglas…abused boys don’t look or behave like that, with their abuser. It’s lovely and a boost to the soul, to see. Ettore was likely in an enviable position.

That’s what BoyLovers naturally do for boys…and Ettore’s adoring face says everything.

[Edit with Addendum]

Just a note for anyone interested. The “Unspeakable” book is currently available on Kindle, so it is being published and distributed in electronic form. I already have my copy of it, moments after learning about it…not to rub the fact in anyone’s face [Sorry Tom!].

It looks like a really good read.

>The “Unspeakable” book is currently available on Kindle

Thanks, Steve, for letting us know. I didn’t think about Kindle. Actually, I finally had an email from UCP yesterday saying the printed book is out now, so presumably my Amazon copy will soon be on its way. Thanks, also, of course, for your very welcome comments.

we have to continue investigating about these authors and their works, my interest was recently entered in Michael Davidson

Ah, yes, Michael Davidson. Many years ago I read The World, the Flesh and Myself; also, Some Boys.

Greetings SteveD, you need to find these books!

Well, then you feel identified with Norman. The age stage of visual brilliance!

Thank you, LTEOGNIS

I did get the book featured in Tom’s post…and it looks like another interesting book has been mentioned.

Although it’s kind of scattered around, I do have a fairly nice library of books on this topic…Glad to have another one. 🙂

Thanks very much Tom for publishing my piece on TikTok!

As for your main article, it seems that intergenerational relationships were really quite a hallmark of more traditional societies, as shown here and for example in ‘Children and Sexuality: From the Greeks to the Great War’ (2007). In our postmodern moment we seem especially to be really clamping down on and repressing any hint of such relationships. Whether Lewis Carroll with Alice Liddell (Platonic as far as I know) or indeed your example here of Norman Douglas with Eric Wolton, it seems to me that a major shift has occurred in our attitudes and values – and furthermore the excuse of ‘child safety’ to rationalise this change can only take us so far.

And this brings me onto the TikTok piece, because it appears children are sexualising themselves and introducing themselves to mature influences like never before now, at precisely the time wider society takes this Puritanical line. So there is a very interesting mix of factors currently in play. And that is why I stated that is important children have their own autonomous voice with which to express their own desires.

But of course *desire* by its very nature and essence can never really be one’s own. Desire can only be formed by the dawning of one’s irrevocable awareness of what others are desiring, or even just paying most attention to. What happens on TikTok is the small person expressing their feelings toward those models they have chosen, towards those they believe must now be ‘closest’ to possession of certain objects in the world..

I also think that the analysis of Heretics must always be attempting to get beyond the mere naming of an imagined enemy, in this case shadows cast by that near mythical figure of the Puritan, and be trying to understand the far broader and deeper culture’s gradual, unconscious eroticizing of “the child”, and the accompanying tacit, unspoken “knowingness” that allows ignorance to pass for wisdom and even for ‘common sense’.

Remember, Zen Thinker – this whole process of eroticization started with constructing the figure of *the child* as walking defence against the multiply mechanical inroads of the French Enlightenment!